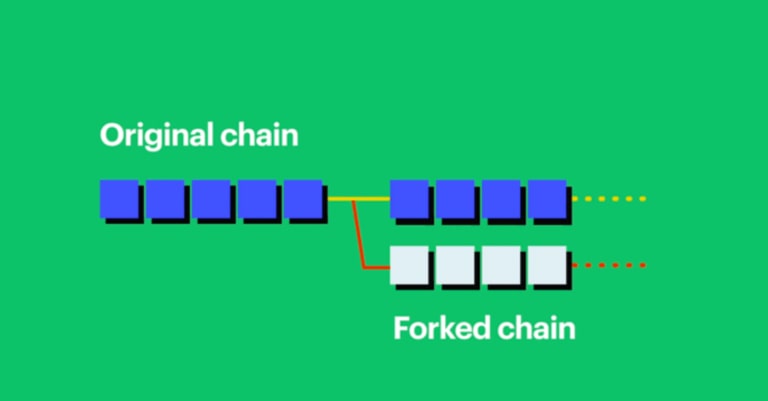

Forks represent changes to the rules of a blockchain protocol and can be either minor (soft forks) or significant (hard forks), affecting continuity or creating branches in the blockchain.

Discussing the evolution of Bitcoin over its more than ten-year existence requires acknowledging both the network’s soft forks and the hard forks that have spawned competing coins from its code.

Thus, understanding soft forks and hard forks is crucial not only for grasping how digital currencies function but also for comprehending Bitcoin’s history and the impact these mechanisms can have on both the network and your Bitcoin holdings.

In this article, we will explain what soft forks and hard forks are, how they work, and what are their differences.

Excited? Let’s dive in!

Table of Contents

What are forks?

In Bitcoin, a “fork” is a mechanism that occurs when there is a change in the protocol’s rules. As we’ve mentioned, this change can be minor (soft forks), affecting the blockchain without completely disrupting it, or it can be significant (hard forks), creating a branch in the blockchain—much like the prongs of a fork, hence the name “fork.”

Forks can occur for several reasons:

- Improvements and updates: As technology and network needs evolve, proposals may emerge to enhance Bitcoin’s functionality. These proposals, if implemented, may necessitate a fork.

- Bug fixes: If a critical error is discovered, a fork may be required to address it.

- Philosophical divergences: Disagreements within the community about Bitcoin’s future direction can lead to forks. This occurred with Bitcoin in 2017 during the Block Size War.

- Attacks or threats to the network: In rare instances, a fork may be essential as a response to an attack or threat to the network.

There are two main types of forks: soft forks and hard forks.

Let’s delve deeper into each type.

What is a Soft Fork and how does it work?

A soft fork is an update that tightens the rules of the blockchain but remains backward compatible; it does not require unanimous consensus to be effective.

This type of update is designed to be backward compatible, meaning that the changes are subtle enough not to conflict with previous rules. Nodes that choose not to update their software to the latest version can still fully participate in the network.

An example of a soft fork could involve further restricting the block size or altering how certain information is stored. Even if some network participants do not adopt the new version, they can still validate and recognize new blocks based on the old rules.

Essentially, a soft fork represents a modest improvement proposal and update that does not drastically alter the network.

Throughout Bitcoin’s history, numerous updates that resulted in soft forks have been proposed and implemented, typically through Bitcoin Improvement Proposals (BIPs).

What are BIPs in Bitcoin?

BIP stands for “Bitcoin Improvement Proposal.” Once approved by the community, a BIP is implemented. Some notable updates that resulted in soft forks include:

- BIP16 (Pay to Script Hash – P2SH): Introduced in 2012, P2SH enhanced the flexibility of transaction creation, allowing for multi-signature transactions. This feature enables multiple parties to authorize a transaction by sending bitcoins to a script rather than a specific address.

- BIP30 (Avoiding Transaction Duplication): This soft fork prevented the inclusion of two transactions with the same transaction ID in blocks.

- BIP34 (Block Version for Duplicate Prevention): Activated in 2013, BIP34 required miners to include both the block version and block height hash in the block header, ensuring a unique chain of blocks by preventing block repetition at different heights.

- BIP66 (Strict DER Signatures): Activated in 2015, this soft fork deemed non-DER signatures invalid, addressing a potential issue with transaction malleability.

- BIP68, BIP112, and BIP113 (Sequence-Based Lock-Time Controls): Introduced in 2016, these BIPs enabled users to set a relative time (rather than an absolute time) after which a transaction could be included in a block.

- BIP141 (Segregated Witness – SegWit): Activated in 2017, SegWit is one of the most significant soft forks in Bitcoin’s history. It addressed issues like transaction malleability and network scalability by segregating the witness component (the signatures) from the main transaction data.

These soft forks were proposed and implemented to enhance the security, scalability, and flexibility of the Bitcoin protocol.

It’s important to note that for a soft fork to succeed, it must gain substantial network support, especially from miners, to be activated and adopted by the majority.

What is Hard Fork and how does it work?

A hard fork is an update that makes the rules more permissive but is incompatible with previous versions, requiring unanimous consensus to avoid splitting the network.

Distinct from a soft fork, it is termed “hard” because the changes are significant/drastic and substantial enough to render it incompatible with earlier versions of the blockchain.

In a hard fork, nodes that have not updated to the new protocol version cannot operate. Updating to the latest version is mandatory; otherwise, nodes will be unable to validate blocks and maintain the network.

Hard forks often result in the creation of a new currency, distinctly different from the original. Since Bitcoin is open-source, various cryptocurrencies have originated from hard forks of Bitcoin, such as Bitcoin Cash and Bitcoin SV. These do not share the same fundamentals as Bitcoin and have faced significant challenges.

In summary, some cryptocurrencies emerged with entirely new code, while others simply made forks by copying and slightly altering an existing code.

Over the years, several hard forks have originated from Bitcoin, often due to internal community disagreements. Here are some of the most well-known hard forks:

1. Bitcoin Cash (BCH):

In 2017, the debate over Bitcoin’s block size was heated. Some wanted the block to be larger, increasing from 1MB to 8MB, thus accommodating more transactions per block, lowering fees, and making confirmations faster. Others wanted to keep Bitcoin as it was.

This period, marked by intense debate and division within the community, was so significant that it was dubbed “The Block Size War,” which later inspired a book.

After extensive discussions, the group that wanted to change Bitcoin’s rules ended up creating a hard fork of Bitcoin, and thus Bitcoin Cash was born.

Over time, Bitcoin Cash has seen a decline in relevance and value, largely because it lacks the same properties as Bitcoin, does not offer a compelling use case, and has not garnered significant demand.

2. Bitcoin SV (BSV):

In 2018, Bitcoin SV emerged as a hard fork of a fork. Bitcoin SV (Satoshi Vision) is derived from Bitcoin Cash, spurred by disagreements over proposed updates to Bitcoin Cash.

Bitcoin SV increased its block size first to 128 MB and later to even larger capacities, aiming to adhere to what its proponents consider the “original vision” of Satoshi Nakamoto.

The project has faced numerous challenges, including several denial-of-service (DDOS) attacks, and is currently struggling to remain viable.

3. Bitcoin Gold (BTG):

In 2017, around the same time, Bitcoin Gold (BTG) emerged as yet another iteration seeking to replicate Bitcoin.

The rationale behind this particular hard fork was to democratize mining by introducing a new proof-of-work algorithm, Equihash, which is resistant to ASIC mining.

Well, as you might know, this cryptocurrency is hardly heard of today.

These examples represent just a handful of the numerous hard forks that have branched out from Bitcoin. Many developers have launched their own variants based on the Bitcoin project. It’s interesting to note that all of them have adopted the “Bitcoin” name, likely in an effort to market themselves as superior alternatives to Bitcoin.

Conclusion

Forks have always been present in Bitcoin, but it is important to note that no matter how much they copy Bitcoin, it is not possible to reproduce its decentralized nature and properties.

People will always opt for the original Bitcoin, which truly has value. In other words, history shows us that making hard forks is often not the best solution.

This is largely because whenever someone proposes an innovative change in Bitcoin that requires a hard fork, the community reacts with caution and skepticism.

Soft forks, in contrast, do not completely overhaul the code and network dynamics. They have been employed for occasional, necessary updates in Bitcoin, always following extensive debate and consensus.

I hope this article clarifies the differences between hard and soft forks for you. If you’re eager to become an expert in Bitcoin, Bitcoin Starter offers comprehensive training to help you delve deeply into this field.

Until the next article and opt out!

Share on your social networks:

One of the leading Bitcoin educators in Brazil and the founder of Area Bitcoin, one of the largest Bitcoin schools in the world. She has participated in Bitcoin and Lightning developer seminars by Chaincode (NY) and is a regular speaker at Bitcoin conferences around the world, including Adopting Bitcoin, Satsconf, Bitcoin Atlantis, Surfin Bitcoin, and more.

Did you like this article? Consider buying us a cup of coffee so that we can keep writing new content! ☕